As you may have noticed I’m a little obsessed with functional programming at the moment. I’ve recently been reading up on bizarre-sounding terms like functors, applicatives and monoids in Learn You A Haskell, only to discover they’re not nearly as incomprehensible as they sound. This post outlines some of the information on functors that this newbie has been able to pick up so far.

Note: One thing I’ve noticed while reading introductory FP material is that each concept seems quite small and understandable, but happens to depend on another million or so small and understandable things. I find this makes it difficult to write about without assuming lots of knowledge, going down a rabbit hole of detail, or glossing over potentially important points. For this post I’ve elected to gloss over details like type constructors and type classes in favour of trying to give a general overview. If you’d like to get the details instead, skip through to the References, starting with Learn You A Haskell.

Types containing values

Many types can be thought of as holding values. For example, lists and arrays can hold integers, strings or other types of values. In .NET, we have the Nullable<T> type, which can hold null, or a value of type T. In Haskell there’s the Maybe a type, which similarly can hold Nothing or an a. We can even think of commands or partially evaluated functions as holding values: once they finish executing they’ll have or return a particular value.

For now, let’s just think of these types as boxes or containers that can hold values of some type.

Mapping over boxes of values

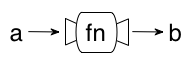

Say we have a function fn which can take some value of type a and return a value of type b. In Haskell we express this as fn :: a -> b, or as Func<A,B> fn in C#.

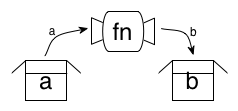

Now imagine we have some sort of box that can hold some quantity of a. We’d like to apply fn to the a we have in the box, and get a new box of b. But fn works on an a, not on a “box of a”, so we need a way of apply our fn inside the box, and then a way of shoving the resulting b into a new box.

The solution is to define a function called fmap which does exactly that. It takes a function (a -> b), and a box of a, and returns a box of b:

-- Pseudo-Haskell

fmap :: (a -> b) -> boxOf a -> boxOf b

// Pseudo-C#

Box<B> Fmap<A,B>(Func<A,B> fn, Box<A> boxOfA);Defining fmap

Now we’ve previously mentioned that these boxes can actually be different types (lists, Maybes or Nullable<T>s). How does fmap know how to unpack and repack all the different types of boxes?

To be able to do this, each type of box needs its own implementation of fmap. Boxes that have a valid fmap defined for them are called functors. Haskell has a lot of these built-in, but we could also define them ourselves:

-- For lists:

fmap fn list = map list

-- For Maybe, which can be either Nothing or (Just someValue)

fmap fn Nothing = Nothing

fmap fn (Just someValue) = Just (fn someValue)

Notice that fmap for a list is exactly the same as normal map. In other words, we iterate over each value in the list, apply the function to each, and then return the new list. For Maybe, mapping the function over Nothing returns Nothing. Mapping over an instance that holds a value gets that value, applies the function to it, and returns a new instance of Just the result.

C#’s type system doesn’t support all the features we need to get a lot of use out of functors, but we can still get an idea of how fmap might look for enumerables and nullables:

public static IEnumerable<B> fmap<A,B>(Func<A, B> fn, IEnumerable<A> functor) {

return functor.Select(fn);

}

public static B? fmap<A, B>(Func<A, B> fn, A? functor) where A : struct where B : struct {

return functor == null ? null : (B?) fn(functor.Value);

}

Graduating from boxes

Notice that fmap preserves the type of box used. For example, if we call fmap on a list, we’ll get another list back. If we call fmap on a Maybe, we’ll get another Maybe back. We never call it with a list and get a Maybe back. If we call our box f, then calling fmap on f a will give us back an f b. The f is preserved.

Rather than using the box analogy, the type f is often referred to as the context, so f a is an a value in the context of f. An a in a context where there maybe be 0 or more values is a list of a. Maybe is a context that may have zero or one a. fmap maps a function from a to b, preserving the context.

Lifting functions is useful

Haskell (and I assume most functional programming languages) has some really interesting ways of putting types together. It is quite common to have simple data types (like integers, strings etc) and functions that operate on them. We can also have more complex data types that can work over many types (they are polymorphic), such as lists of a or Maybe a (where a can be an integer, string, function or even another type of list). Because this polymorphism is so common, it would be nice to be able to reuse functions that work on simple types in different contexts, and that’s exactly what functors let us do.

This is known as lifting a function; transforming a function like a -> b to work in another context, like f a -> f b.

For example, we can use lift a standard integer operation like (+1) to work on Maybe Int:

ghci> fmap (+1) (Just 10)

Just 11

ghci> fmap (+1) Nothing

NothingOr apply a standard string function to a Maybe String:

ghci> fmap reverse (Just "hello world!")

Just "!dlrow olleh"

ghci> fmap reverse Nothing

NothingAnd then of course there is the familiar mapping over a list (as mentioned earlier, map, or Select in .NET, is just fmap for list):

ghci> fmap (*2) [1..10]

[2,4,6,8,10,12,14,16,18,20]

csharp> new[] {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10}.Select(x => x*2);

{ 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20 }As a pure functional language, Haskell eschews code with side-effects, which includes some innocuous-sounding things like reading or writing to files. To work within this restriction, side-effects can be wrapped up in types like IO a. Because IO is a functor, we can use fmap to work with the value inside the IO context without having to explicitly pull out the value (so side-effects stay neatly wrapped up in their IO box). Say we wanted to read an integer from STDIN, here’s how it would work with and without fmap:

doubleInput = do

input <- getLine

let enteredNumber = read input :: Int -- read string as int

let double = 2 * enteredNumber -- (2*)

return $ show double -- show int as string

doubleInputWithFmap = fmap (show . (2*). read) getLine

Finally, functors are just one part of a large hierarchy of type classes. Other type classes like applicative functors and monads build on the properties of functors to provide their own interesting capabilities.

Well-behaved functors

We’ve seen that functors are types that can can have functions mapped over them, thanks to an corresponding implementation of fmap. That’s the bulk of it, but there are also two formal properties that these fmap implementations need to have in order for a type to act as a functor.

The first is that mapping the identity function over a functor is the same as calling the identity function directly on the functor. id is the identity function in Haskell, the C# equivalent being x => x. The identity function takes an argument and returns it, unchanged.

fmap id a = id a

-- Example

ghci> id (Just 42)

Just 42

ghci> fmap id (Just 42)

Just 42The second is that composing two functions then mapping them needs to give the same result as mapping each function in turn. In other words:

fmap (f . g) = fmap f . fmap gTypeclassopedia’s entry on functor laws mentions that satisfying the first law automatically satisfies the second. Which is good, because to me the first is a lot easier to follow. :)

These properties aren’t enforced by the type system, but we need to make sure our functors have them or else our functor won’t behave like all the other nice functors. These properties guarantee that fmap preserves the structure (or context) of our functor.

References

- “Functors, Applicative Functors and Monoids”, Learn You A Haskell

- “Functor”, Wikipedia

- “Map (higher-order function)”, Wikipedia

- “Typeclassopedia”, HaskellWiki

- “Applicative functors”, Haskell Wikibook